View Unix man (help) pages in Preview

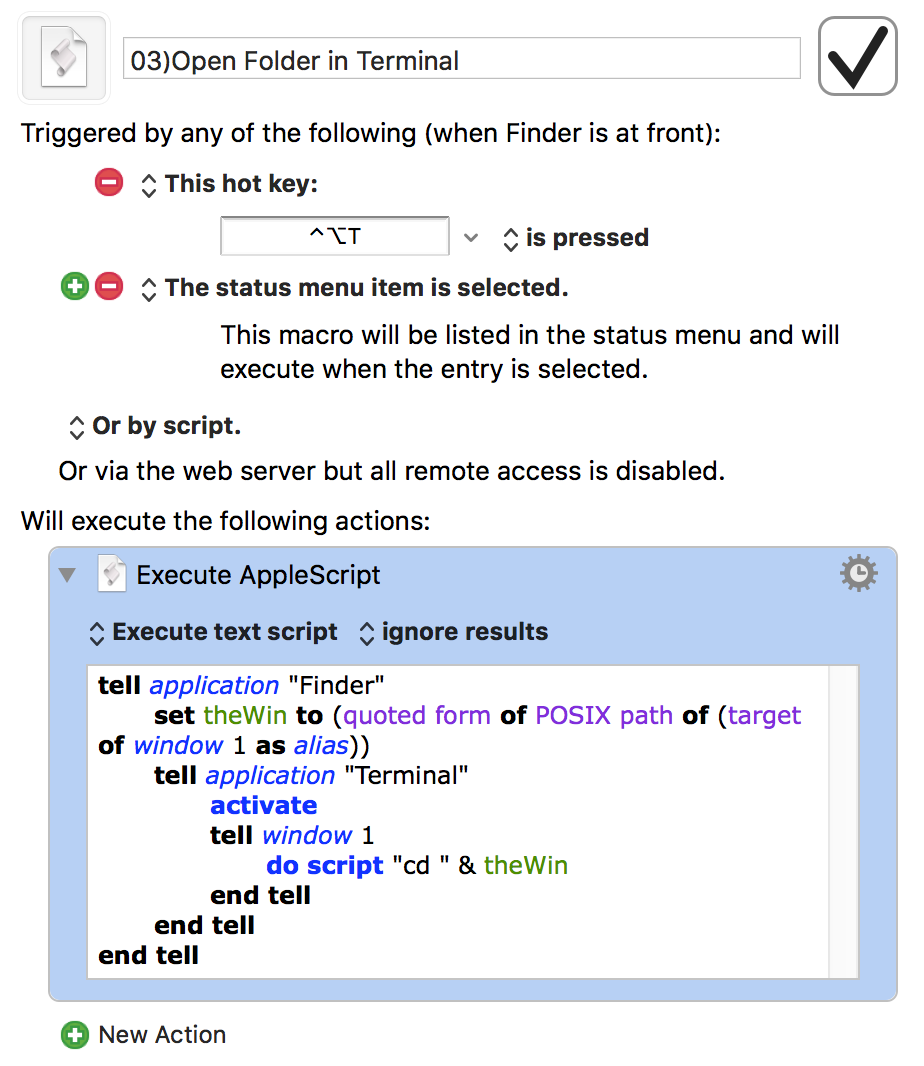

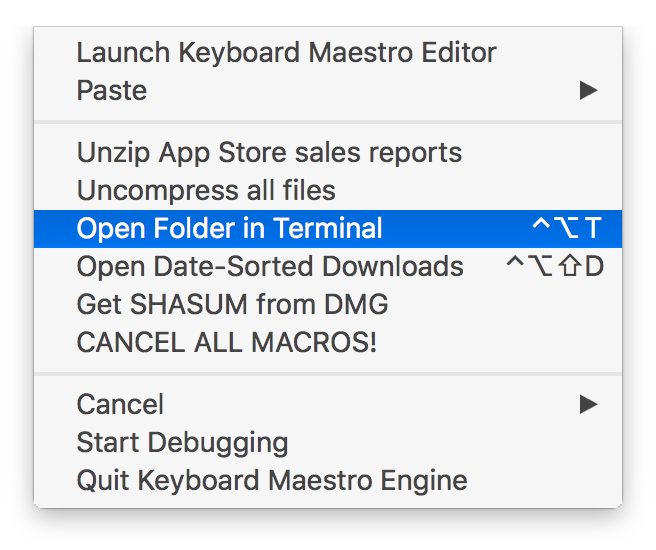

Today's tip goes well with yesterday's tip, which explained how to open any Finder item's folder in Terminal via Keyboard Maestro. Once in Terminal (and sometimes even when not in Terminal), I'll often want to check out the man page (help) for a given command.

You can do this directly in Terminal with man [name of command], of course, but then it opens on top of whatever you were working on, and you have to read it in Terminal. You could use another tab or window, but you'd still be reading in Terminal. There are times, too, when I'm writing about the Unix side of macOS, so I'm not even in Terminal, but still want to view a man page.

My solution to this problem is two different ways of doing the same thing: I open man pages as nicely-formatted PDFs in Preview. The method I use to get to that point depends on if I'm working in Terminal or not.

Update: I've modified the script and macro so that they properly handles two-argument man commands, such as man 3 printf.

In Terminal

Based on an old Mac OS X Hints tip, I created a very simple shell script:

1 2 3 4 | #!/bin/sh cmd=$@ man -t $cmd > "/tmp/$1.ps" open "/tmp/$1.ps" |

The key to this little script is the -t option on the man command. From the (hehe) man man help file, here's what that does:

-t Use /usr/bin/groff -Tps -mandoc -c to format the manual page,

passing the output to stdout. The default output format of

/usr/bin/groff -Tps -mandoc -c is Postscript, refer to the

manual page of /usr/bin/groff -Tps -mandoc -c for ways to

pick an alternate format.In other words, the -t converts the help page into a PostScript file, which is something that Preview can easily open (which is just what the last line of the script does).

I named this script preman, because it uses Preview to open man pages. Once saved, I made it executable (chmod 755 preman), and I can then open any man page in Preview by typing, for instance, preman bash.

The output is nicely formatted, and by opening the man page in Preview, my Terminal session is uninterrupted. A quick adjustment with Moom, where I have a saved layout to position Preview and Terminal, and I can scan the man page while working in Terminal.

But what about when I'm not in Terminal? For that, I basically implement the same shell script, but with it set up to run within a Keyboard Maestro macro.

A couple years back, I

A couple years back, I